The surprising history of the locket

By Rachel Church

What is a locket?

A locket is a jewel linked with memory. It can be a private sentimental item or an object associated with public success.

Most importantly, it is a container – a jewel made to hold a precious item, perhaps a portrait, a lock of hair, an item of sentimental importance or a relic.

Lockets can be used in most forms of jewellery. They hang from a necklace or are set in the clasp of a bracelet or the bezel of a ring. They can be brooches, pins and even buttons.

Modern lockets are generally worn by and marketed to women. However, historically, they were worn by women, men and children. They were made from precious metals and gemstones for the rich. Mass produced lockets made from cheaper materials were available for a wider group of wearers. Whether richly set with gems or very humble, they were often intensely sentimental and personal jewels.

Holy relics: the locket in medieval Europe

The early history of the locket is linked to that of reliquary jewels. These small pendants were made to contain holy tokens such as fragments of bone or hair from a martyred saint.

Faithful Christians believed that these relics could heal the sick and perform miracles.

Wearing a relic close to the body was a sign of faith and served as an amulet to protect the wearer against both physical and spiritual evils.

This enamelled ‘Agnus Dei’ pendant once held a disc of wax which had been blessed and stamped with an image of a lamb and cross. These were made from the candle used by the Pope during Easter celebrations. They were a powerful amulet, especially for pregnant women.

Reliquary jewels were also used as diplomatic gifts and status symbols. In 1238, the French king Louis IX bought the Crown of Thorns from Baldwin II, the Emperor of Constantinople. He used individual thorns as diplomatic gifts, one of which was set into an amethyst and enamelled locket now in the British Museum.

A holy relic was a treasure beyond price and needed an appropriate container. Reliquary jewels were often made of gold, enamelled and set with pearls and gemstones. They were worn at the highest levels of society – the 1380 inventory of Louis d’Anjou lists ‘petits reliquaries d’or a porter sur soy’ (little gold reliquaries to wear upon your person).

A beautiful pendant, set with an amethyst cameo of the Virgin and Child was given to the monastery of St John on the Greek island of Chalke by a cleric named Arsenius. The back of the jewel has a cross shaped locket which probably held a fragment of the True Cross or a relic closely associated with Christ. The inscription reads ‘Thou hast redeemed us by Thy precious blood, nailed to the cross’.

The great English writer Geoffrey Chaucer told his readers that to win a fair lady’s love, you should send her ‘letters, tokens, brooches and rings’. Jewellery was a well understood way to earn a place in someone’s heart. A medieval German brooch in the shape of the letter E (probably the initial of the wearer or the donor) is set with the figure of a man, piercing his own heart with arrows. The inscription on the back can be translated as ‘Fair lady, may I always remain close to your heart’. The hinged lid lifts up to reveal a hollow space which may once have held perfume or a sentimental token.

Rewards and renown: the Renaissance and 17th century locket

Renaissance lockets were often portrait jewels (known as boîtes a portrait in French). These jewels made prestigious court or diplomatic gifts. They were offered as a sign of favour and treasured as family heirlooms.

The outer case of the locket was designed to be seen. It could be enamelled with a monogram, an ornamental design or set with a cameo, gemstones or a medal. The locket often held painted miniatures by the finest artists of the day such as Nicholas Hilliard, Isaac Oliver or Jean Petitot.

Designs for pendants,Ornements d’orfèvrerie, Louis Roupert, Metz, ca. 1668

© Bibliothèque de l’Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art

Locket with monogram of Henrietta Amalia von Anhalt-Dessau, The Netherlands, ca. 1690

© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Receiving a jewel set with the portrait of a ruler was a great honour. Portrait jewels could be official gifts, for a visiting ambassador or the prince of another realm. The first recorded instance of a miniature being used in diplomacy between two states was in 1526, when Marguerite, duchesse d’Alençon sent pictures of her two sons, set in finely worked gold lockets, to the British king Henry VIII. The children were hostages at the court of Emperor Charles V and Marguerite hoped to gain Henry’s support in reclaiming them.

Pendant with portrait of Mary Stuart, wife of William II of Orange, ca. 1645

© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Portrait jewels might also be granted to recognise an individual service. In 1611, the British king James I gave a locket set with his painted miniature in a jewelled case to Thomas Lyte as a reward for painting the king’s family tree. He also gave a fine diamond chain hung with his portrait to the Duchess of Lennox as a thank you for making ‘broths and caudles’ for an invalid. Wearing a jewel with the ruler’s image was a wonderful way to show your closeness to the court and the favour you enjoyed.

Lockets could also hold more intimate images, like this double locket which holds the portraits of an unnamed man and woman, probably a husband and wife. This is a smaller and more personal version of a double wall portrait.

Love in life and death: the locket in the 18th century

The word locket began to appear in the English language in the mid 17th century – other European languages used a variation on medaillon. Contemporary paintings often show the locket worn as a pendant from a chain or ribbon around the neck or hanging from a belt.

Designs for lockets or pendants from the Nouveau Livre de Serrureries, Paris 1709

© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Women, men and children continued to wear lockets. Crime reports from the early eighteenth century report small children wearing gold or silver lockets on coral necklaces. Coral was a protective amulet and the locket may have held the picture of a parent, a lock of hair or a religious image.

Lockets continued to be court gifts, set with portraits or medals of the ruler.

The sentimental locket – ‘Il core vi dono – this heart I give you’

In Mozart’s opera ‘Così fan tutte’, Guglielmo gives his heart, in the form of a locket, to Dorabella to replace the portrait of her former lover, Ferrando. The symbolism of the locket is clearly shown as Guglielmo sings ‘This heart I give you, lovely idol mine/ but yours I want also. Come give it to me’. By giving Dorabella a locket, Guglielmo is laying claim to her affections.

The locket’s outer case was often enamelled with a romantic scene, or with a personal monogram while the precious image or relic was hidden inside.

Giving someone a locket was an intimate act, especially if it contained a lock of hair or a miniature picture. In Marivaux’s play Les Fausses Confidences of 1737, when asked for a picture by her lover Dorante, Araminte exclaims ‘Give you my portrait? But that would be the same as saying I love you!’

The woman seated in this painting by Nicolas Lavreince holds up a locket at arm’s length, perhaps to comfort herself for her lover’s absence.

Part of the charm of a locket was that it could be there when the lover was absent, a token to be cherished and kissed. The hero of The Lover’s Luck, a 1696 play by Thomas Dilke, owned ‘a Locket of your Ladyship’s Hair, which he always wore next to his heart […] kissed a thousand times […] not without a frequent Current of Tears’. Mourning jewels often included hair. A little heart shaped locket from 1706 is set with hair on one side and on the other, an engraved skull and date of death.

Political lockets

Political lockets might hide the wearer’s sympathies by concealing a portrait of a ruler or a politician inside a neutral case, like those worn by supporters of the exiled Stuart monarchy in Britain. In Revolutionary France, Madame de Genlis showed her move, from being a member of the court inner circle to an ardent Revolutionary, by wearing a locket, set with the word Liberty in diamonds and enclosing a piece of the destroyed Bastille prison.

Many jewels were made to commemorate Admiral Horatio Nelson, the British hero of the Napoleonic Wars. Wearing a jewel set with his portrait or a lock of his hair was a sign of national pride and a way to associate yourself with a significant historical moment.

Locket with portrait and hair of Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1805

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Love, fashion and novelty: the locket in the 19th century

Lockets were at the peak of their popularity in the 19th century. By 1871, the Queen magazine declared that ‘Lockets … are considered indispensable with morning costumes.’

They were very widely worn by both sexes and at all ages, from the small child to the old age pensioner. Women usually wore lockets around their neck on a chain or ribbon, pinned to the bodice as a brooch or perhaps set into the clasp of a bracelet or a ring. They might also hang from the waist on a watch-chain or a chatelaine. Men’s lockets were typically private jewels, worn with a chain or ribbon under the shirt or perhaps fixed to a watch-chain and tucked into a waistcoat pocket.

A locket is a complex object. A disassembled model for a locket by the British artist Robert Field shows a typical construction. The framework of the locket is made of carefully constructed parts which fit together to make a secure case for the image and panel of hair, protected by layers of glass. A ‘double-box’ locket was a more expensive and complicated design, containing two internal compartments for portraits or hair.

The industrial revolution brought machinery powered by steam into the jewellery trade. Locket parts made through die-stamping and with steam rollers were cheaper to produce than those created by hand. They became available at lower prices to a wide range of customers.

The love locket

Coversheet for ballad ‘You, only you’, 1895

© The New York Public Library

Placing a picture of your lover, family member or child inside a locket made it a precious and personal object. The invention and popularisation of photography made portraits available to those who could not afford a miniature painting.

Hair was such a popular addition to lockets that it became the subject of music hall jokes, such as the following:

‘I presume you carry a memento of some sort in that locket of yours?

Precisely; it is a lock of my husband’s hair.

But your husband is still alive?

Yes, sir, but his hair is all gone.’

A lock of hair was a precious reminder of an absent person, whether separated by physical distance or through the permanence of death.

Lockets were often gifts between lovers and might even become evidence in a broken engagement or divorce case, such as that of Sir John Tollemache Sinclair in 1877. Sinclair discovered his wife’s infidelity when he found out that she wore a locket with her lover’s photograph underneath her clothing.

Many grooms gave lockets to their brides as wedding or engagement gifts, often made personal through the use of devices, initials or coats of arms. Lockets become a favourite plot device for writers – to show clandestine love affairs, lost children, and reveal family secrets. In a magazine story written in 1901, Colonel Lockhart designed his own locket as a gift to his bride, decorated with a rose made of rubies and set with his own portrait, which his bride kissed, describing it as ‘my dearest jewel’.

Perhaps the story was inspired by bridegrooms such as John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute? He designed the bridesmaids’ jewellery for his wedding himself. When he married Gwendolin Fitzalan-Howard in April 1872, he designed lockets in the shape of a shield enamelled with his and Gwendolin’s coat of arms. Each jewel was set with diamonds and pearls.

Mourning lockets

When Princess Augusta’s beloved former governess, Lady Charlotte Finch, died in 1813, the Princess wrote to her daughter saying that ‘I take the liberty of offering You a locket which I hope You will do me the favour to accept – It is to contain the Hair of Your invaluable Mother’.

A locket with the image of a child could be very meaningful at a time when children’s lives were fragile. A newspaper story from 1910 shows a conscience-struck thief returning a gold miniature locket to a London couple – the newspaper reports that it held the portraits of their two little boys and ‘the parents were particularly sorry to lose the locket because the elder of the two boys only died a short time ago and the miniature could not be replaced.’

This black enamel and gold mourning locket is engraved “My second son Gerardus, Dec. 6th 1864.” It must have been made for one of his grieving parents who placed a lock of his hair inside the locket.

Mourning locket, 1864

Inscribed on inner gold disk with “My second son Gerardus, Dec. 6th 1864.” Inscription surrounded by outer enamelled circle by engraved inscription: “In memory of.”

© Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

The locket as a gift

Because lockets were so easy to personalise, they continued to be useful and common gifts. British Queen Victoria gave jewellery throughout her life, often putting greater emphasis on its personal aspect rather than the overall value.

Lockets were also popular as leaving or retirement gifts and are frequently mentioned in newspaper reports. American postal inspector John Clum, who set up the first postal service in Alaska, was given a watch-fob and locket, set with a diamond, as a retirement gift in 1911. The inside of the locket was engraved with the name of 14 New York postal inspectors and holds a piece of red, white and blue fabric.

Novelty lockets

The versatility of lockets made them ideal novelty jewels. A locket set with a miniature English dictionary (the back of the locket held a magnifying glass) could hang from a chatelaine or watch chain as a convenient and entertaining accessory.

Locket set with miniature English dictionary, late 19th century.

© Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

The little gold suitcase, engraved ‘Somebody’s Luggage’ opens up to show a series of tiny photographs. These were made to mark the wedding of the stage performers Charles Stratton, known as General Tom Thumb, and Lavinia Warren in 1863. The couple were actors of short stature who were part of P.T. Barnum’s travelling show and performed at the highest levels of society, including for Queen Victoria. This ingenious locket was a fun souvenir of the wedding and an entertainment for the wearer’s friends.

Celebrity lockets

Owning an object or lock of hair associated with a famous person was a way to link yourself with an illustrious person or a shared national history. Pieces of fabric and buttons joined hair and portraits to create secular relics. The Confederate Museum in Richmond, Virginia, displayed lockets with hair from the Civil War soldiers General Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis. They also had a locket containing a piece of the first Confederate flag with a lock of Davis’ hair. In a more lighthearted way, an admirer of the French composer Charles Gounod placed one of his trouser buttons into an expensive gem set locket.

The locket in the 20th and 21st century

Although the locket wasn’t as ubiquitous in the twentieth century as it had been in the nineteenth, it still retained a place in fiction and in real life. The designs of lockets followed the movement of twentieth century art. Fashionable lockets were made using the flowing lines of Art Nouveau, the geometry and colour of Art Deco and the fantasy and fun of the 1950s and 60s.

Enamel continues to be a popular way to add colour and appeal, sometimes used as a transparent layer over an engraved locket or painting a picture on the locket’s case.

Locket pendants with guilloche enamel and design drawings, Victor Mayer, c. 1900

© Victor Mayer archive

Amusing lockets can be made in imaginative shapes. Designers at Victor Mayer created a tiny house with an opening door and a locket shaped like a photograph frame which slid open to reveal a tiny mirror.

Tiny house with inscription >There is room in the smallest hut< after a well-known poem by Friedrich Schiller. Pendant with mirror with inscription >my sweet<

© Victor Mayer archive

Lockets were still worn by men on watch-chains in the early twentieth century. They were frequent presentation gifts for retirements, weddings or new jobs. The locket could also be an important sentimental object during the war years. Loving couples wore each other’s portraits and parents kept the image of their soldier sons close.

Mourning locket

Victor Mayer, Pforzheim, first World War

© Victor Mayer archive

In Pforzheim, the jeweller Victor Mayer, who lost two of his three sons during the First World War, sold large quantities of silver and black enamel mourning jewellery. These sombre jewels became a way for families to mark the enormous losses of the war years.

Jewels continued to mark family ties in the second World War. American president General Dwight D. Eisenhower gave little charms to his wife Mamie to add to her bracelet throughout their marriage. One of the most charming was a little gold box locket, engraved with her initials, which opened up to show a photograph of Eisenhower in uniform. The couple were separated for nearly three years during the Second World War – perhaps her little locket pendant was a small consolation?

Marking romantic and family love

The locket continues to be the perfect way to keep the memory of your love close to your heart. A pretty locket set with a photograph came into style in the nineteenth century and has never gone out of fashion. Adding an engraved motto or monogram can make this most personal of jewels even more unique.

Locket sample collection, Victor Mayer, ca. 1905

© Victor Mayer archive

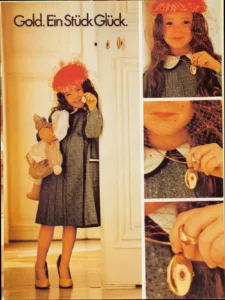

Advertisement of the International Gold Council with locket and ring by Victor Mayer, inscription >Gold. A piece of happiness<, ca. 1985

© Victor Mayer archive

People continue to wear lockets set with the pictures of their loved ones, children or parents, set in an elegant and attractive jewel. The use of lockets as presentation gifts or signs of political allegiance has faded but the romantic locket has never lost its place. Victor Mayer’s lockets combine traditional craftsmanship with elegant modern designs, continuing the rich history of the jewel.

Whether it’s a vintage locket set with an up to date photograph or a jewel commissioned as a gift of love, the locket retains its charm. Wearing a locket today is an expression of a personal style that combines vintage fashion with a modern nonchalance.

Rachel Church is a jewellery historian and researcher who is particularly interested in the stories behind jewels. She is the author of ‘Rings’ (V&A/ Thames and Hudson 2017) and ‘Brooches and Badges (V&A/ Thames and Hudson 2019). She lectures regularly and writes about jewellery at thelifeofjewels.com.